On the 9th of October 2021, Vincent Kemme, founder of the Institute ‘Biofides’ for biology and faith, was invited to give a talk on ‘End of Life issues in the Low Countries, at the occasion of the National Meeting of the Catholic Medical Association in Portugal, helt in the Catholic Faculty of Medicine in Lisbon. Here follows a written account of his presentation.

Lisbon, 9 October 2021

Introduction

It is a privilege and an honour for me to speak to you, today, at this National Day for Catholic Physicians in Portugal, at the Catholic Faculty for Medicine in Lisbon. Allow me to introduce myself to you briefly, before touching upon the topic you asked me to speak about during this conference: Euthanasia in the Netherlands and Belgium.

I am a biologist from the Netherlands, trained in the higher secondary education for young people, preparing for university studies in medicine and other disciplines, mostly the natural sciences. I taught in the Netherlands and in Belgium and at the European Schools in Brussels. During my academic studies at the university of Utrecht in the Netherlands, I had a life changing experience of Gods existence, due to the encounter with a new ecclesial movement, the so called ‘charismatic renewal’. Before, although raised in a catholic family, I had left the Church and had no religious practice, as a result of lack of understanding and interest. From that experience on, in 1980 to be exact, the relationship between faith and biology became a central theme in my intellectual journey. Science and faith, evolution and creation, but also the ethical questions around abortion, contraception, euthanasia, but also ecology, had become unavoidable due to the great changes in the culture in the sixties and later on. For that reason and out of pure curiosity, I pursued additional studies in theology, philosophy and bio-ethics.

In 2009, having moved to Belgium (more precisely: Flanders) with my wife and six children, I had to decide to put an end to my teaching career for ‘health reasons’. Part of the problem was the way I was supposed to teach human sexuality and procreation that even in catholic schools were supposed to be a course in contraception. But there were other reasons too. At that point, I decided to start my apostolate ‘Biofides’, in which I try to provide reasonable answers to any question a student might ask me once they found out that I was a catholic biology teacher.

Only a few months later, a physician from Brussels, the president of the Catholic Medical Association of Belgium, Prof. Dr. Bernard Ars here present amongst us, invited me to joint the board of the bilingual medical association, in order to deepen, or even correct, the ‘mindset’ of the board, regarding bioethics and the teaching of the Church. Dr. Ars and I are working together now for more than a decade, today in his capacity as president of the World Federation of Catholic Medical Associations with its office in the Vatican. And here I am, speaking to an audience of medical students and doctors in Lisbon.

Biofides researches first of all the relationship between faith and science, philosophy being the playfield where both human intellectual endeavors meet and enter into a dialogue, without confusing theological and scientific argumentations, nor separating them as irreconcilable. A proper metaphysical and ontological view of reality and proper understanding of epistemology are needed to bring harmony between faith and science(1). This leads to a philosophical anthropology, a vision of man, from which one can come to a reasonable understanding of morality and bio-ethics (2). Biofides addresses itself not only to the medical field, but also to the world of education, science, society as a whole, and the Church itself, where, unfortunately, a lot of confusion appears to exist.

Euthanasia

The questions concerning ‘the end of life’ were certainly not the questions that interested me most. How can a biologist be interested in ending the phenomena that he studies: biological life? The origins of life, the human species within the context of biological life on earth and in the universe, its ontological statute, its procreation and embryological development, its intellectual, moral and spiritual faculties, its eternal destiny far beyond the realm of our earthly existence: those are the questions that had my interest. This fascination for biological, and therefore also human life, is what makes us wonder at what is clearly a mystery: something that can be known but also surpasses. No biologist has a particular interest in death, although even death is a fascinating topic for the biologist. No physician decided to study medicine, in order to learn how to kill a patient that is entrusted to his care, although death is a reality for every doctor, something he has to have an answer to, although maybe not a medical answer. So the topic can not be avoided as humanity appears to take it upon itself to do the opposite of what one would expect a biological being to do: put an end to its life or having someone else, in a white coat, do so. In the past, such a person would be considered mentally ill. Today, he or she is respected for the way this person makes use of his or her autonomy. So I will share with you my thoughts, based on the reality of twenty years of legalized euthanasia in the Low Countries, The Netherlands and Belgium. I will do this in three parts: some facts about the actual situation, some socio-cultural considerations and some suggestions for a strategy for catholics in medicine.

The Netherlands and Belgium

Is was in 2001 and 2002 respectively that in the Netherlands and Belgium laws allowing euthanasia, although under strict conditions, passed the democratic process and were adopted in the respective parliaments. Since then, the number of – officially registered – cases of euthanasia and medical assisted suicide (I will not make a distinction between the two, here) have only risen. In 2020, almost 7.000 cases have been registered in te Netherlands, a country with 17,4 million inhabitants. This was the result of an augmentation of 9,1% between 2019 and 2020 only, which does not promise much good for the numbers of 2021 that are at this point not yet available. On the total number of deaths in one year, the number of cases represents about 4,1 percent.

In Belgium, a country of 11,5 million inhabitants, a small majority of which is Dutch speaking, a big minority in number is Frans speaking, the numbers of registered medically provided deaths was 2.656 in 2019 and 2.444 in 2020, which represents about 2,5 percent of all deaths per year. It is notable that 77 percent of these cases where registered in Flanders, the Dutch speaking region of Belgium, and only 23% in Brussels and Wallonia, the French speaking part of the country. This is, in my view, an indication for the cultural differences between the the two parts of the country, where the Flemish tend to be far more orientated to the north, the Netherlands, whereas Brussels an Wallonia are culturally far more influenced by the south: France. I will come back on these cultural differences and their impact on these numbers in what follows.

According to a study of the British Medical Journal, about 50% of the cases of euthanasia or medically assisted suicide are committed illegally, so not registered, which would mean that up to 8 or 9 percent of the deaths in the Netherlands are medically provoked, and probably in comparable numbers in Flanders. This is completely in line with the public opinion, and the messaging in the main stream media, that medically assisted dying has become a perfectly acceptable way of ending ones life. Moreover, there is the slippery slope of always adding categories of people that can be euthanized legally: not only the somatically terminal patients, suffering in an ‘unbearable way and without medical perspective’, but also psychiatric patients, infants, and in the near future maybe also people that are ‘tired of life’, detainees, and some day, the handicapped… A new word has appeared in the Dutch media: ‘Euthanasiasm’(3) an amalgamation of euthanasia and enthusiasm, where even secularist public opinion seems to start asking questions about the desirability of the actual situation. But signals of a return to – in our view – ‘moral normality’ in the near future are still lacking. The main legal battle today for physicians and all healthcare workers is: the right to conscientious objection.

Some socio-cultural considerations

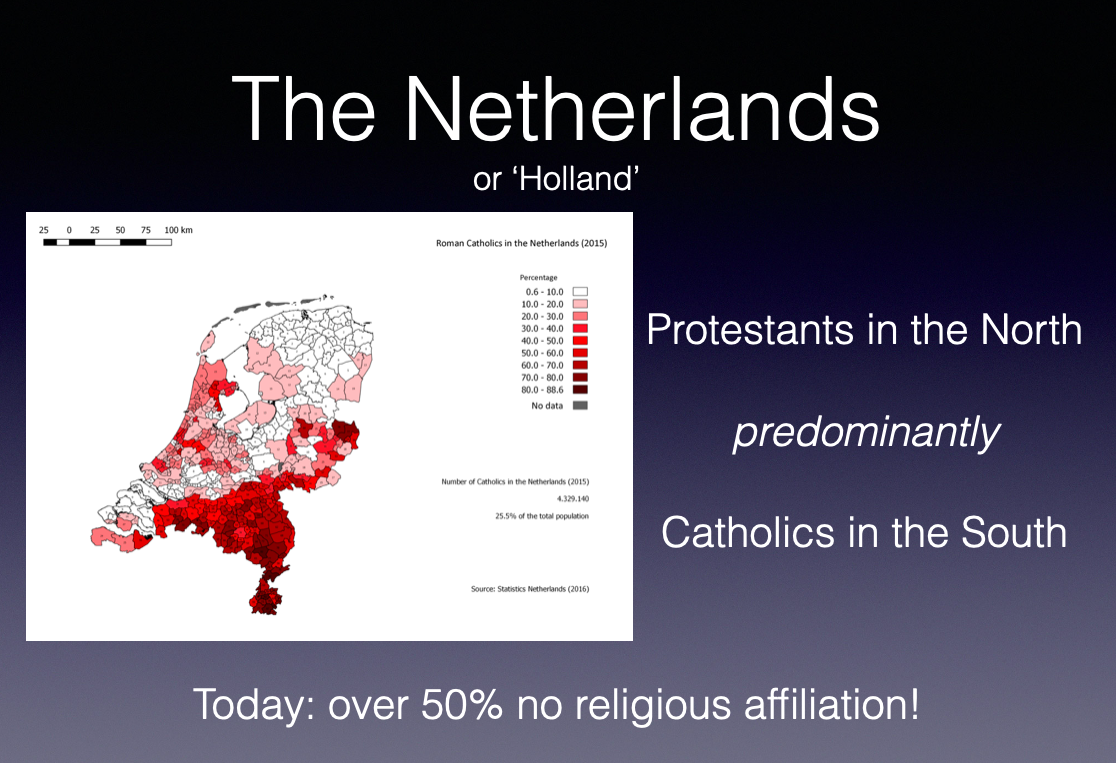

The major sociocultural change that we have witnessed is the dramatic religious decline since the sixties, especially in the Netherlands and – in its footsteps – Flanders. In the Netherlands, today, over 50% of the population says to have no religious affiliation of any sort, catholicism, protestantism, islam or judaism. This has lead to an extremely secularized society, characterized by materialism, relativism, subjectivism and pragmatism. Any religious affiliation is suspect of being ‘fundamentalist’ or ‘extremist’, especially since the appearance of ‘fundamentalistic islam’, accompanied by terrorism. As all ‘organized religions’ are simply ignored, distinctions between catholicism and (fundamentalist) islam are no longer made in the public discourse.

The Netherlands has been dominated by a calvinistic, very divided protestantism (where Germany has been dominated by lutheranism), which has led to theological and moral subjectivism and relativism, lacking a unifying religious and moral authority as in catholicism. On top of that the secularization from the last five decades and the result is what we have now, despite a traditionally relatively strong position of the catholic christianity in the south-east of the country. In Belgium, a country strongly divided by the linguistic and therefore cultural problems between ‘Francophone’ en ‘Flemish’ Belgians, the influence of protestantism is far less. Flanders has always remained under the influence of catholicism (under the Spanish, Austrian and French role) and Francophone Belgium, strongly under the French influence. The secularizing forces come especially from the ‘free thinkers’, in the slipstream of the French revolution and freemasonry. Because of the linguistic and therefore cultural bonds between Flanders and the Netherlands, the impact of the very strong secularization in the Netherlands has been enormous, in the last decades. In the end, both countries have taken the lead in secularization and moral relativism in Europe, and most countries of Europe seem to follow their example, even Ireland and Poland. Portugal does not seem to be able to escape from this tendency.

Sexual revolution

An aspect of this pragmatic but in some cases immoral attitude is the massive refusal of the Church teaching on contraception, after the introduction of ‘the pill’. What is more materialistic and pragmatic than taking a pill in order to solve what is perceived as a physical problem, namely: fertility? In a materialistic worldview, moral objections are hard to think of – what is morality – even if it means the introduction of a culture of death, as John Paul II would call it later. As the pill, as well as other forms of hormonal contraception, is an act against life, against a life giving act of love, the twofold finality of spousal love, it is immoral even before being abortifacient in its double effect. This opens the door to abortion, as the human embryo does not have the dignity anymore that it has ontologically. On top of this: the failing of contraception in to many cases, methodologically or practically, the numbers of abortions will rise. And if death as a solution to our problems can be accepted in the beginning of human life, why not at the end? So it was just a matter of time and euthanasia would become acceptable.

As through contraception procreation or fertility became separated from spousal love, sexual enjoyment became a goal in itself, without any other finality than personal and relational joy. This could not other than lead to the sexual revolution that we have known in the sixties and that is still dominating our culture. And when sex has no other goal than personal or relational intimate enjoyment, why then limiting it to one person, why still promising fidelity, why not with a person of the same sex? What is the importance of biological sex anyway? Let us change our ‘gender’ if we ‘feel’ that we are living in ‘the wrong body’. Introducing death as a solution to our problems, means the denial of basic biological understanding of our species and medical ethics in one stroke. The sexual revolution has destroyed, to a great extend, the ‘Imago Dei’: ‘male and female he created them’ (Gen. 1) (4), and therefore – in a way – a ‘real presence’ of God, in the form of the married couple and the family, within society. The result is ‘a real absence’ – to a certain extend – of God in the culture, also called: secularism. Euthanasia is just a symptom of this cultural disease.

Some strategies for catholics in medicine

Taking into account that the legalization of euthanasia, also in Portugal, seems to be unavoidable at this point(5). Many other countries prepare for legalization so it seems very difficult if not impossible, to ‘turn the tide’ in the near future. What can be our attitude towards this reality? The first thing is: ‘to get over it’, by accepting reality as it is. It is normal that we, as catholics, deplore this development, but it seems useless to me to remain embittered by the situation. Rather, we will have to become that ‘creative minority’ (A. J. Toynbee) (6), that is inventive in finding concrete solutions and make beneficial proposals for society, to offer alternative solutions in stead of a profoundly negative attitude, both in the working place as well as in society.

Our creative presence in society should focus on three levels of human activity: faith, reason and practice.

Faith

Challenging situations are always an invitation, for a catholic, to deepen his faith. This means: renewing our personal relationship with Jesus Christ, through personal prayer, eucharistic adoration, and a deeply lived sacramental life. And this should never be done all alone, but in some kind of community. Therefore, Sunday Mass may not be enough and participation in a prayer group or faith community seems to me a prerequisite for spiritual growth and empowerment. Personal guidance by a priest or an experienced and trustworthy spiritual guide belongs to our basic needs for a strong en deeply rooted life in Christ, ‘without Whom we can do nothing (Joh, 15,5). It is through prayer and life in Christ, that God Himself can act through us, by the creativeness of his Holy Spirit. It would be arrogant to think that we, human beings, could solve our problems only by ourselves. That would be a form of Pelagianism (7), as if we do not really need Gods grace. On the other hand, we can do a lot, if we do what God inspires us to do, guiding us by his Providence. As a willing instrument in Gods hand, we can ‘move mountains’. So let us not lose hope and never resign to what God wants from us. Let us be His true disciples.

Another aspect of our faith life is compassion, charity that goes as far as loving our enemies. And in a post-modernistic society, as in the Low Countries, we have many ‘enemies’, in our families, neighbourhoods, and as colleagues: people who have embraced convictions and practices, or political views, that go directly against our religious and moral beliefs. Love them with your whole heart and distinguish between the person and his of her way of life. Hate the sin, but never the sinner. Discern the reasons why someone is not against euthanasia and be understanding, without judgement. And be patient with one another. People, ourselves included, need time to come to other conclusions. God is patient with us. Let’s be patient with our contemporaries.

So as a catholic we are called to be a witness to what we believe in: the God of life and love. This means a supernatural love for the world we live in, our colleagues, family members and even our politicians! Therefore, we need Gods anointment, so be renewed in the grace of our confirmation: the gift of the Spirit that has beard so many fruits, the lasts decades, and in the history of the Church. The Holy Spirit, the most neglected person of the Holy Trinity, gives us the strength to remain faithful, the insight in what we believe and why, the love that we need for our neighbors, and the courage to go out, ‘come out of the closet’, ad bear witness of our faith in an attractive and convincing way for others. We are called to be apostles, also as a doctor.

Reason

A second level of human activity concerns reason, our intellectual capacities. It is my experience, although living in a country where euthanasia has become legal for twenty years, that I still need to deepen my understanding about why this is immoral, why – for instance – ‘mercy killing’ is a false notion, or which arguments can be used in our dialogue with contemporaries who think (and act) otherwise. For instance: why limiting our argumentation to the immanent aspects of end of life question: the unbearable suffering, the so called ‘quality of life’, the dangers of ‘the slippery slope’. Why not also introducing the notion of transcendence in human nature, which means that if a human person would have an ’immortal soul’, euthanasia may have consequences in what is called ‘the afterlife’, not only for catholics who believe in the afterlife, but also for those who do not believe in anything that transcends human life ‘before death’. If immortality and the afterlife are real, atheists will also have an afterlife. The thousands of systematically documented testimonies of ‘Near Death Experiences’ over the last five decades seem to ‘proof’ that this is not only a reality of human existence, but that death comes also with an evaluation of the way we have lived our lives before death. These testimonies show that euthanasia is not ‘recommended’ (8). Is it morally acceptable that we limit our argumentation to the life before death, the immanent, as if the afterlife and the possibly timeless consequences for euthanasia do not exist? Do I need to be a priest or a theologian to make this point? Is my own catholicity, as a baptized christian and physician not enough, even though I will immediately admit that the afterlife is outside my competence as a physician? Is it not an argumentation, from reason rather than faith, that needs to be be considered?

It is the knowledge of our faith and our understanding of its reasonability, that, in the end, will convince. We need to understand the basic theological en philosophical starting-points and our ethical principles, not only our medical specialty. At the basis of reasonable medical ethics is a human anthropology that is adequate for describing the whole human nature, of every single human being: a person, a composed of the material and the spiritual. And it goes without saying that we need te excel in medical expertise and skills.

Practice

Practically speaking: catholic doctors in the Low Countries speak about ‘creative resistance’ when it comes to morally challenging situations. The appeal to conscientious objection seems to be the corner stone of their opposition to euthanasia and other moral reprehensible acts. This can and should be accompanied by refraining from any judgment of our colleagues and the power of the example: nothing less than sainthood.

Love and truth go together, in christian behavior. No truth without love ‘for your enemy’. No love for you colleagues in disguising completely the truth. It is a daily exercise to balance the two. Also very important is the distinction between the person and his of her beliefs and practices as mentioned above. Never judge the person, only an opinion or practice. ‘Being right’, theologically or morally, in you convictions, is easy; getting the other person to admit that you are right, ‘getting right’ if one can say so, is far more challenging. It requires a lot of prayer, love, discernment in how to speak or act in a particular situation, a lot of love and patience with the other, and maybe, we will fail. A christian doctor is like any christian ‘in the business of’ witnessing, not of convincing. We respect the God given freedom of the other person, even to believe the most immoral things. Our testimony is one of words and deeds: nothing worse than a catholic who’s speech is not confirmed by his actions and – especially – his reactions. A real christian is recognized by his reactions, not his actions. That’s what they call sainthood. Our convictions must ‘incarnate’ and become attitudes, also to be called virtues.

In the case of a demand of euthanasia, the interpersonal relationship with the patient is key to an understanding of the ‘question behind the question’: fear for pain, loneliness, abandonment, etc. Catholic doctors in the Low Countries also warn for the danger of being instrumentalized by the patient, the familie, of even by the hospital. Our creative resistance can be hard. Let us not forget that baring witness in the New Testament is very often linked to the reality of martyrdom. It would be an illusion if we would think of witnessing only in terms of giving a good example. Witnessing comes with suffering, and in some cases, it may cost as much as your assignment. So let us be realistic, not naive, but also not afraid. In my case, as a biology teacher, my beliefs had great consequences, for even catholic schools wanted me to teach contraception. In the end, I had to put and end to my career as a teacher. Today, I speak to you, physicians and students in medicine, at a Catholic Faculty of Medicine. Our ways are not always Gods ways.

So my point is that if we want to change the culture and politics, we should begin with changing ourselves. Five decades of radical secularization, as we lived in The Netherlands and Belgium… It took christianity 300 years to christianize the Roma Empire. So we will have to strive, but also to be patient. Our children, an American priest said to me in Belgium, will reap the fruits of our striving. So please do not lose hope and don’t let the probable legalisation of euthanasia, if you can’t stop it, rob you of your joy: the joy you have in being a child of God and – hopefully, – an excellent physician.

Notes

(1) Dominique Lambert: Sciences et théologie – les figures d’un dialogue, Edition Lessius, 1999.

(2) Peter Kreeft: A History of Moral Thought – Modern Scholar Audiobook, 2003

(3) Dessaur, C.L, and C.I.C. Rutenfrans – Mag de dokter doden? Argumenten en documenten tegen het euthanasiasme [May the Doctor Kill? Arguments and Documents against Euthanasiasm]. Amsterdam: Querido, 1986.

(4) Pope John Paul II, Michal Waldstein (translator): Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body, Pauline Books & Media 2006

(5) “For a second time, President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa of Portugal has rejected a bill that would have legalised euthanasia and assisted suicide in the country. Parliament is now unlikely to be able to override the President’s veto before elections of new Parliament members are held in late January of 2022. https://www.liveaction.org/news/president-portugal-rejects-euthanasia/.

(6) “The phrase, which Benedict XVI has used for several years, comes from another English historian Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975). Toynbee’s thesis was that civilisations primarily collapsed because of internal decline rather than external assault. “Civilisations,” Toynbee wrote, “die from suicide, not by murder.” https://catholicexchange.com/benedict’s-creative-minority/

(7) Pelagianism is a heterodox Christian theological position that holds that the original sin did not taint human nature and that humans have the free will to achieve human perfection without divine grace.

(8) Dr. Patrick Theillier: Expériences de mort imminente – Un signe du ciel qui nous ouvre à la vie invisible – Edition Artège, 2015

Recommended literature:

Euthanasia: Searching for the full story. Experiences and Insights of Belgian Doctors and Nurses

Timothy Devos

The book offers a new critical analysis of euthanasia and is written by health care professionals in Belgium – where euthanasia has been legal for 20 years. Provides a real-world multidisciplinary approach with contributions of hematologists, psychiatrists, palliative care doctors, nurses and an ethicist. It presents lessons learned from the application of laws in countries that have legalized euthanasia.

Vincent Kemme

Former biology teacher from the Netherlands, living in Belgium, founder of the Biofides institute for biology and faith, editor in chief of Acta Medica Catholica, bulletin of the Catholic Medical Association of Belgium, Assistant to the President of the World Federation of Catholic Medical Associations (FIAMC, Rome). Husband, father and grandfather.